John Adams’ Role In Framing The Massachusetts Constitution: An Arduous Yet Fascinating Process

By quincyhistoryEditor’s Note: This article was written by William Cunniff Jr., an archival intern with Quincy Historical Society during the summer of 2024. He is a recent graduate of Archbishop Williams High School in Braintree.

Has your curiosity ever been piqued when you took a peek from your passenger window at the obscure and strangely shaped monument in Freedom Park? If so, then I suppose that you have wondered, at least for a few moments, what the monument represents. Interestingly enough, directly adjacent to the monument lies a plaque that displays an excerpt from the Massachusetts State Constitution, which after much trial and tribulation, was adopted in June of 1780. The plaque also provides a thorough explanation of the symbolism of the oddly formed sculpture. According to the plaque, the three main drafters of the document, John Adams, Samuel Adams, and James Bowdoin, are reflected through the three large blocks of granite which are meant to assist in shifting a person’s focus towards the center of the monument. I also find it necessary to mention that the rather hard texture of the granite is intended to convey that these three drafters’ opinions evolved over time, due to their frequent communication with one another while trying to create a finished product. However, it is also worth noting the positioning of the stone fragments, since they face one another, highlighting the fact that although differing ideas might clash, the new constitution could foster cohesion among the people as it represents compromise.

Right: Overhead view of the plaque which describes the meaning of the monument, and the symbolism of the sculpture in Freedom Park.

[Images courtesy of the author.]

In fact, the Massachusetts State Constitution is the longest living and still active written constitution throughout the world, and although it has been amended and revised numerous times since its original passage, the general framework for the document remains unaltered for the most part.[i] As stated earlier, John Adams, one of our hometown Founding Fathers, played a fundamental part in its creation. While many of us understand John’s influence on the ideals and principles that would eventually be enshrined in the national Constitution, his major role in the drafting of the Massachusetts state governing document is one of his lesser-known achievements. As a Quincy native, although I, myself have driven by this statue on Burgin Parkway many times, I failed to recognize the significance of this often-unnoticed piece of Quincy history. I wear the badge of growing up in Quincy with honor and pride; and this monument is certainly yet another addendum to the vast collection of history compiled in Quincy over the years. I am undoubtedly sure that more historical discoveries are right in front of our eyes and faces, ready to be uncovered.

Adams’s background, as a well-known and well-respected lawyer, allowed him to transition into the world of politics, later becoming Washington’s vice president and our second president. Due to his professional experience as a lawyer, it is certainly unsurprising that he would become a venerated political figure and an activist for balanced constitutional government. While he was studying at Harvard, many of his teachers and peers suggested that he enter the field,[ii] and in 1758 after his sponsor, Jeremiah Gridley, testified to his legal promise, his ultimate goal was accomplished.[iii]

Early in his legal career, after his business began to earn profits, he wrote a diary entry on August 1st of 1761, and it displayed a blueprint for the argument that he would make to a jury in the case of Prat v. Colson.[iv] Ultimately, the British Constitution was vital to John when advancing his viewpoint in this case. His usage of the British Constitution manages to illustrate his deep respect for both the law and constitutional ideals.

John Adams represented the plaintiff, Prat, who sued Colson, the administrator of the Bolster estate. In Adams’ blueprint for the jury, Prat asserted that when he worked as an apprentice for Bolster, his master, the terms of his relationship were not completely fulfilled. Since Prat, as a young boy, was destitute and had no active father figure in his life for financial support, his mother created an agreement where he would be Mr. Bolster’s apprentice for 11 years. In Adams’ notes, he stated that Bolster promised that the boy would become literate, numerate, and learn the weaver’s trade; however, the plaintiff claimed that none of these contract requirements were fulfilled.[v]

Later in Adams’ argument, he also referenced the tenets of the unwritten British Constitution, suggesting that anyone who fell under certain categories such as “weak” or lacking a father would receive favor from the law. Due to Adams’ deep respect for teaching, he could more passionately and fervently argue his case, knowing that the British Constitution greatly encourages educating oneself.[vi] Adams then concluded his argument on paper, with a recognizable comparison for the jurors when he discussed a connection between popular elections and citizens perusing their Bibles. He stated that a citizen has to read for themselves, not only their Bibles, but other materials as well, and then apply the messages that were learned to their own lives, when making important decisions, such as selecting a politician.[vii] Adams also highlighted the fact that no overarching power or government should compel or coerce a citizen to think or conduct themselves in a certain manner, thus illustrating the fact that he espoused freedom of conscience.

As the colonies were considering declaring independence from Great Britain in 1776, the colonies realized that if they made this choice, then it would be necessary to create their own individual constitutions to solidify their sovereignty and establish a functioning form of government with written laws. At the behest of his colleagues, John Adams wrote one of his most famous political works, known as “Thoughts on Government”. Many of his ideas from this short paper were not only incorporated into the Massachusetts Constitution, but they also influenced the framework for the national Constitution which would be passed 11 years later. The most famous quote for which Adams had a major affinity refers to the country of England being “an empire of laws, and not of men.” As many can see, this quote emphasizes Adams’ belief that individual power cannot remain unchecked or unlimited, and that the law serves as the natural force to guide society.

One of the most famous and still relevant ideas discussed was the notion of a bicameral, or two-house legislature which Adams heavily supported.[viii] As evidenced by his choice, Adams did not intend that the power to pass legislation should be concentrated within a single body of people, as he understood that it would provide disproportionate influence to a certain group. John’s influence on the federal structure can also be seen through a hypothetical scenario. For example, if only the House existed, then an inordinate amount of sway would allow the more populous states to overpower the smaller ones, similar to how a Senate-only government grants unfair influence to smaller states, since not all people in the larger states could receive adequate representation from only 2 senators.

Adams urged the creation of both an upper house and a lower house so both ordinary citizens and the upper class could coexist and flourish side by side. After drafting “Thoughts on Government”, he presented this paper to the Continental Congress in the month of May. In the coming years, “Thoughts on Government” served as the guidebook that other states utilized when drafting their own constitutions, thus making Adams’ constitutional impact not only profound, but truly indispensable as well.

The journey towards the actual drafting of the Massachusetts State Constitution first began in 1776, the same year when “Thoughts on Government” was penned, and Americans obtained their independence from Great Britain. At first, the state legislature made the suggestion to the people to vest it with the authority to draft a constitution on their behalf. However, this proposal was encountered with strong indignation from Concord and many other towns, which claimed that such an idea would contradict democratic principles and fail to protect citizens against government infringement on their liberties.

Later in April of 1777, a compromise was reached, thanks to the input of Lexington, along with the support of Pittsfield, which led to an announcement of the state legislature. In this announcement they declared that the next elected legislature would possess the task of drafting the state constitution and then the individual towns would decide whether to accept or reject the proposed draft. The second part of the compromise, which granted the towns great latitude in the matter, managed to satisfy the demands of both Pittsfield and Lexington. The people substantially voted against the original version from 1778, when it was distributed to the towns, by a tally of approximately 4 to 1. The main reasoning behind the aversion of the people towards the 1778 Constitution was that it lacked a bill of rights.

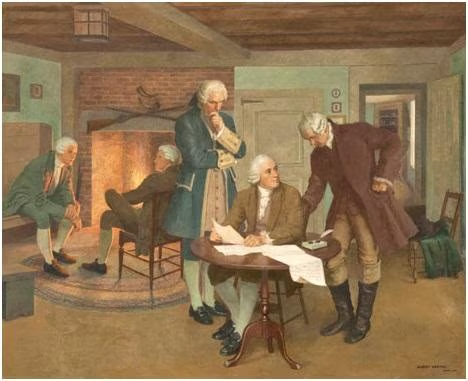

In June of 1779, in order to address and allay these citizen concerns, the state legislature announced that a constitutional convention would take place a few months later. In September, at the convention, an approximately 30-member drafting committee was formed, for the purpose of devising a declaration, or bill of rights, while also creating a plan for a balanced government. This committee of about thirty selected a smaller subcommittee composed of 3 individuals, John Adams, Samuel Adams, and James Bowdoin, all of whom mutually concurred that John should pen the new draft. John persisted and persevered through two months of dedication to this task, at his own home in Quincy, and arrived at a conclusion when on the 1st of November, the convention possessed his draft. The convention slogged tirelessly for 16 days after obtaining Adams’ draft, and they vowed to regather in early January after they decided to take a temporary hiatus.

Two months later, the convention sent the slightly edited draft to each individual town at the beginning of March of 1780. After the draft had been delivered, the convention took another brief three-month respite, and the members regathered at the start of June. After tireless consideration for two straight weeks, on June 16th it was determined and joyfully proclaimed that the necessary ⅔ approval mark for each constitutional provision had been reached and that on October 25th, the new governing document became established law.

[i] Taylor, Robert J. “Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution.” 1980. American Antiquarian Society: Worcester. Pg. 317.

[ii] Bernstein, R.B. “The Education of John Adams.” 2020. Oxford University Press: Oxford. Pg. 27.

[iii] Bernstein, R.B. “The Education of John Adams.” 2020. Oxford University Press: Oxford. Pg. 31.

[iv] Bernstein, R.B. “The Education of John Adams.” 2020. Oxford University Press: Oxford. Pg. 34.

[v] Bernstein, R.B. “The Education of John Adams.” 2020. Oxford University Press: Oxford. Pg. 35.

[vi] Bernstein, R.B. “The Education of John Adams.” 2020. Oxford University Press: Oxford. Pg. 35.

[vii] Bernstein, R.B. “The Education of John Adams.” 2020. Oxford University Press: Oxford. Pg. 36.

[viii] Bernstein, R.B. “The Education of John Adams.” 2020. Oxford University Press: Oxford. Pg. 109.

Post navigation

5 thoughts on “John Adams’ Role In Framing The Massachusetts Constitution: An Arduous Yet Fascinating Process”

Comments are closed.

Very well written and very interesting.

Thank you Mr. Cunniff. That monument has always puzzled me in its abstract message.

What a great article! I’ve passed the monument hundreds of times, and always assumed it was an assemblage of odd pieces left over from the granite quarries. Thank you for all the information and the explanation of what the pieces all stand for.

Another interesting article. I never realized the granite was actually a monument!

Great article Will!!